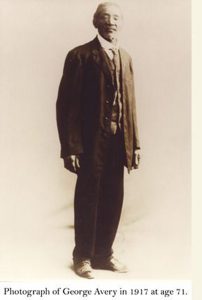

by Katherine Calhoun Cutshall (North Carolina Room, Pack Memorial Library)

George Avery was enslaved in Asheville from the time of his birth until he fled Buncombe County with Union General George Stoneman and his troops in April 1865 and enlisted in the Union Army at Greenville, Tennessee. At the time, George was a 19 year old blacksmith who followed his master, William McDowell, to the front to serve as his hand servant. Some oral traditions suggest McDowell encouraged George to follow Stoneman, understanding that the Confederacy was bound to lose, so that his trusted slave would receive a pension after the war.

George enlisted with the 40th United States Colored Infantry Regiment, a group of African American Soldiers comprised of men from most of the Southern states, but primarily North Carolina, Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama. Their primary role found them working to guard and repair railroad lines destroyed by the war and moving goods to assist Federal Troops that finally had a stronghold in East Tennessee.

After the end of the Civil War, Avery returned to Asheville. McDowell eventually sold Avery a small portion of his estate, and named him caretaker of the South Asheville Cemetery. Avery became involved with a number of social and political groups in the African American community, including the Freemasons, the Temperance Union, and the Young Men’s Institute.

A number of other men from Buncombe County served in the 40th USCT and returned to Asheville to live and work. Other men who joined the 40th deserted the unit within just a few days, using the military as a gateway to total freedom. Muster rolls indicate this was a common practice.

These soldiers lives after the war were similar to Avery’s. Some, like Julius Ragswell and Squire Washington returned to work for their former masters, while maintaining involvement in the up and coming political and social circles for African Americans during reconstruction and the turn of the century.

For the majority of his life after the war, he was the primary caretaker for the only public cemetery for African Americans in Asheville. There was no plan or map of the cemetery; Avery committed the locations of the graves (often unmarked by a headstone) to his memory. Today, the cemetery is the property of St. John “A” Baptist Church and is maintained by the church and the South Asheville Cemetery Association. George Avery died at the age of 96.

Courtesy of Katherine Calhoun Cutshall who works in the North Carolina Room at Pack Memorial Library