Our first production this season, The Fire of Freedom, follows the story of Abraham Galloway on his journey from slave to senator. Based in eastern North Carolina, he was a fierce abolitionist and political adversary for the Union. Like Galloway, many slaves and free people of color are erased from history books, leaving their stories untold.

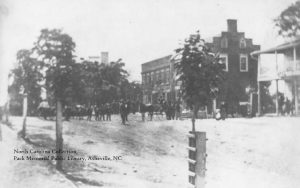

When discussing this history, two figures come to mind for librarian Katherine Calhoun Cutshall who works in the North Carolina Room at Pack Memorial Library. Cutshall explores the narratives of George Avery and James Casey, whose complex history is foreign to many folks in the region and beyond. In this article, we offer a glimpse into these lives and their connection to Asheville and Appalachia.

George Avery and the 40th USCT

George Avery was enslaved in Asheville from the time of his birth until he fled Buncombe County with Union General George Stoneman and his troops in April 1865. He enlisted in the Union Army with the 40th United States Colored Infantry Regiment, a group of African American Soldiers comprised of men from most of the Southern states. Their primary role found them working to guard and repair railroad lines destroyed by the war and moving goods to assist Federal Troops. After the end of the Civil War, Avery returned to Asheville a free man and became involved with a number of social and political groups in the African American community, including the Freemasons, the Temperance Union, and the Young Men’s Institute.

READ MORE

James Casey, A Citizen of Necessity

At North Carolina’s constitutional convention in 1835, legislator James W. Bryan contended that he did “not acknowledge any equality between the white man and the free negro” rather he stated, “the free negro is a citizen of necessity.”

The ruling in the petition case of James Casey, a free black man from Haywood County, reflects Bryan’s sentiment. Casey experienced the complications of his legal status as a free man of color when he was arrested and brought into Confederate Service in 1864.

Ultimately, James Casey’s fate came down to the whims of white confederates. In the end, Casey served in some capacity with the waning Confederate army, but did so under the social circumstances allowed to him because of his race. James Casey, neither fully slave nor fully free, experienced the American Civil War as a “citizen of necessity.”