This blog post is one of a three part series for our current production of Thurgood at the North Carolina Stage Company, running April 26 – May 19. The show details the life of Thurgood Marshall and the run coincides with the 70th anniversary of the Brown v. Board of Education decision – a landmark case that ruled against the segregation of public schools in the United States. This blog series works to situate Asheville in the history of American desegregation and the Civil Rights Movement. This blog explores the effects of desegregation in Asheville’s public high schools and nearby universities on the community.

In the early 1960s, Asheville City Schools attempted to avoid full compliance with desegregation by leaving the decision of which school children attended up to individual families. This effectively kept all Black and all white schools distinct and open, and the court system eventually stepped in to require an active integration plan from the City. The school board had one Black member during this period, Dr. John Holt. Many Black schools were closed to avoid “excess classrooms” and students were required to bus long distances to historically white schools. City school enrollment steadily plummeted, Buncombe County school population numbers rose, and suburban development increased dramatically.

Before the integration of high schools in the Asheville area, the all Black Stephens-Lee High School, affectionately known as the “Castle on the Hill,” boasted a highly qualified team – 20 of the 33 teachers employed there had Master’s degrees. Black Americans flocked to the education field in the early twentieth century and public school teachers made up the largest professional sector in North Carolina at the time. Stephens-Lee opened its doors in 1923 and was the only high school for Black children in Western North Carolina. Stephens-Lee teachers made an annual salary of $933 while white teachers in the area received salaries of $1,783. Stephens-Lee quickly gained a reputation for academic excellence and was well known for their sports and music programs. One effect of the Brown v. Board of Education decision was the loss of Black educators as Black students were predominantly sent to what were previously white schools. North Carolina, and the Asheville area, were no different. Local efforts have been made to track the careers and lives of the educators that once taught at Stephens-Lee, and information can be found at the Stephens-Lee Community Center, on route for one of the Hood Huggers Community Tours, and in the written work: “The Faculty of Stephens-Lee High School: A Tribute” by Zoe Rhine and Joel Newman, a copy of which is available at the Buncombe County Special Collections.

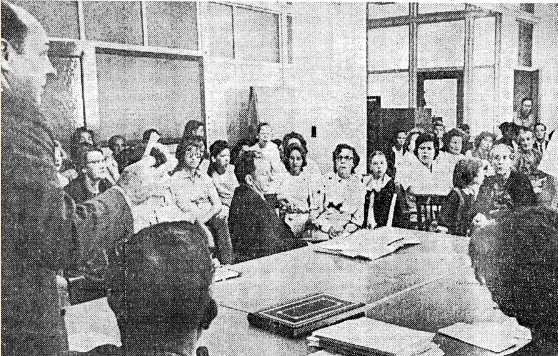

Black high school students were expected to integrate into what were previously all-white high schools – the formation of Asheville High School was the result of students from South French Broad (the replacement for Stephens-Lee before integration efforts began in full) joining the previously all white Lee Edwards high school in 1969. While the facilities at previously white high schools were nicer, Black students migrating to their new schools experienced a loss in the quality of their education. This manifested in the loss of many of their Black teachers, and resources such as Stephens-Lee’s music and sports programs. Tensions rose as Black students received harsher punishments for minor infractions, objections to the white teacher assigned to teach Black history, and a noticeable lack of training for Black hair in the cosmetology program. After the wrongful expulsion of Leo Gaines for violating the dress code (he wasn’t wearing socks) on September 29, 1969 – Black students organized a protest for the treatment they’d received since integration. In response to the students refusing to disperse until they were heard, Asheville High School called in the police. Leo Gaines was never allowed to return to school and though the City denied any accounts of police brutality, police chief J.C. Hall admitted that officers struck students with batons. Tensions continued throughout the 70s and culminated in counts of violence against Black students and continued protests at the disproportionate treatment for white versus Black students. Ultimately, the City’s response to Black students and their demands to be heard fueled antagonism between white and Black Ashevillians. Their only concern was the maintenance of appearances at the cost of progress during integration.

Warren Wilson was one of three choices for a college education in the region in the time leading up to desegregation. They set a precedent that their peers would struggle to maintain – the university actively sought international students from Africa and elsewhere throughout the thirties and admitted its first Black student, Alma Shippey, from the WNC region in 1952. Georgie Powell became the first Black graduate in 1958. Later, universities from across the state would write to Warren Wilson for guidance on desegregating their own campuses. Integration at the other universities stalled for much longer, as epitomized in the University of North Carolina Asheville. UNCA was originally known as Asheville Biltmore College and was founded in 1936. Etta Whitner Patterson became the first Black student at Asheville Biltmore College in 1962, and Francine Delany the first Black graduate of the institution in 1967. Patterson later stated that she “was selected by leaders in the community to break the segregation barrier at UNCA. It was an enormous responsibility for an 18 year old.” Delany went on to become a teacher and later a principal for Asheville City Schools. In 1970, the entire UNC system was cited for noncompliance with Title IV of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, but a concrete plan for desegregation remained in the planning stages until 1978. 1986 saw the first Black faculty at UNCA: Charles and Dee James, Dwight and Dolly Mullen, Gwen Henderson, and Anita White-Carter. Black enrollment nearly reached 8% in the same year, but by 2005 had dropped to 2%.

To learn more about the efforts Black students to access quality education, Black teachers, and the effects of desegregation across high schools and college campuses in the Asheville area, check out the Center for Diversity Education’s With All Deliberate Speed and the African American Heritage Resource Survey by the City of Asheville. Both sources offer visuals, context, and first person accounts of the lived experiences of those who lived during this period of Asheville’s history.